This article was originally printed in Permaculture Design Magazine issue #110, Winter 2019, the Permaculture Ethics issue.

As permaculture becomes more popular and gains greater recognition with a mainstream audience here in North America, I find that it’s helpful to have your “elevator speech” ready-to-hand to quickly define it when it comes up in casual conversation. I usually speak about permaculture in concrete terms at first using keywords like “edible landscaping” or “edible ecosystem design,” while dancing around the more abstract idea of whole systems design. If the people I’m talking to seem interested and want to talk more, then I move up in abstraction to talk in terms of “ethically bounded ecological design framework.” Normally, you hear that there are three ethics to permaculture: Earth Care, People Care, Fair Share. Sometimes you hear it as Earth Care, People Care and Future Care. The first two ethics are easy to explain, easy to understand and they usually only need a sentence of explanation. A lay person can quickly and intuitively grasp the meaning behind Earth Care and People Care.

Fair Share or Future Care are less easy to explain or understand in this 30-second “elevator speech” scenario in an American context. Even when I have a longer format to explain permaculture to an interested audience, that third ethic needs 2-3 sentences because it attempts to unite two separate ideas into one ethic. Indeed, compared to the first two ethics, the third ethic can sound almost abstruse: “set limits to consumption and reproduction and redistribute surplus.” As permaculture gains more attention from a more mainstream lay American audience, we can’t have the core philosophy of our design discipline sound abstract.

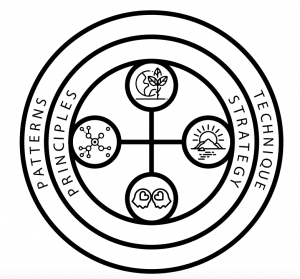

One of the things that sets permaculture apart from other design disciplines is the fact that it is an ethically bounded system of ecological design. Think of a set of concentric rings or a spiral. At the center are the ethics. Spiraling outward are the design principles, pattern literacy, goals, strategies, and finally the concrete aspects like techniques and tools. Ethics are at the core of permaculture design, and I think they are in need of a slight revision for an American audience.

One of the things that sets permaculture apart from other design disciplines is the fact that it is an ethically bounded system of ecological design. Think of a set of concentric rings or a spiral. At the center are the ethics. Spiraling outward are the design principles, pattern literacy, goals, strategies, and finally the concrete aspects like techniques and tools. Ethics are at the core of permaculture design, and I think they are in need of a slight revision for an American audience.

Here in the United States, our self-conception of being the exception to all rules (both ecological and economic) runs very deep. For ease of explanation and understanding and to directly challenge the American resistance to accepting any kind of limits I propose breaking that third ethic into two. I was originally introduced to the concept of four ethics  in permaculture by this image drawn by someone named Christine and found in the wilds of the internet. I don’t know the original creator of this image, but the signature looks like it has an original creation date of 2002. It keeps the rhyming convention because everyone seems to like that. So the four ethics in this proposal are Care, Care, Share, Aware: Care for the Earth, Care for the People, Share the Surplus, Aware-ness of Limits. Based on David Holmgren’s ethics, and broke into four pieces, this is the gist:

in permaculture by this image drawn by someone named Christine and found in the wilds of the internet. I don’t know the original creator of this image, but the signature looks like it has an original creation date of 2002. It keeps the rhyming convention because everyone seems to like that. So the four ethics in this proposal are Care, Care, Share, Aware: Care for the Earth, Care for the People, Share the Surplus, Aware-ness of Limits. Based on David Holmgren’s ethics, and broke into four pieces, this is the gist:

Care for the Earth – rebuild and regenerate ecosystem health (after Holmgren). This icon represents the earth and all the biological and ecological processes that keep us alive on this spaceship. In this case it’s focused on plants, but it also includes all insect, bird, wildlife, and elements that make for a healthy ecosystem. The imperative here is to take responsibility and do our part to regenerate the health of ecosystems immediately all around us.

Care for the Earth – rebuild and regenerate ecosystem health (after Holmgren). This icon represents the earth and all the biological and ecological processes that keep us alive on this spaceship. In this case it’s focused on plants, but it also includes all insect, bird, wildlife, and elements that make for a healthy ecosystem. The imperative here is to take responsibility and do our part to regenerate the health of ecosystems immediately all around us.

Care for the People – look after self, kin and community; and treat all beings with respect. This icon shows two people with love on their minds and in their hearts. This love extends to all human people who are alive now or who are about to be born. It extends to future generations and it extends to all the people: human people, tree people, finned people, feathered people, furry people, creepy-crawly people, etc. As Holmgren says, “If people’s needs are met in compassionate and simple ways, the environment surrounding them will prosper.” It’s a natural complement to Earth Care and should include frameworks of social justice.

Care for the People – look after self, kin and community; and treat all beings with respect. This icon shows two people with love on their minds and in their hearts. This love extends to all human people who are alive now or who are about to be born. It extends to future generations and it extends to all the people: human people, tree people, finned people, feathered people, furry people, creepy-crawly people, etc. As Holmgren says, “If people’s needs are met in compassionate and simple ways, the environment surrounding them will prosper.” It’s a natural complement to Earth Care and should include frameworks of social justice.

Share the surplus – in times of abundance, share with others and invest in the first two ethics. This ethic is about a principle of generosity. At different seasons of the year, or in different seasons of one’s life you might experience abundance. Maybe its an abundance from the garden or an abundance of time, money, attention or just hugs. Share that abundance and invest it as you see fit into the first two ethics. This icon is a representation of the “pay it forward” ethic as goodwill spreads throughout a social network in direct and indirect ways.

Share the surplus – in times of abundance, share with others and invest in the first two ethics. This ethic is about a principle of generosity. At different seasons of the year, or in different seasons of one’s life you might experience abundance. Maybe its an abundance from the garden or an abundance of time, money, attention or just hugs. Share that abundance and invest it as you see fit into the first two ethics. This icon is a representation of the “pay it forward” ethic as goodwill spreads throughout a social network in direct and indirect ways.

Aware(ness) of limits – set limits to consumption and reproduction on this finite planet. Everyone knows the sun sets every day. Everyone knows there are boundaries to an island. This icon represents those common knowledge boundaries to remind us of the limits inherent on this finite planet. And even if the sun should set on our species, we should still commit to live an ethical life while we can.

Aware(ness) of limits – set limits to consumption and reproduction on this finite planet. Everyone knows the sun sets every day. Everyone knows there are boundaries to an island. This icon represents those common knowledge boundaries to remind us of the limits inherent on this finite planet. And even if the sun should set on our species, we should still commit to live an ethical life while we can.

With this slight adjustment, it makes the ethics easier to explain to a lay audience new to permaculture. At one explanatory sentence apiece (with only one semicolon), it also makes the concepts behind the ethics instantly accessible to that lay audience, largely achieved by separating those concepts originally condensed in the Fair Share ethic. As permaculture becomes more popular here in North America, it becomes a conceptual and technical solution set to which people look in times of crisis. The ethics must be central to maintain the integrity of the idea and the solutions that go along with it. The ethics are the axiological foundation of permaculture’s attempt at re-membering an ecological culture rooted to place and acting in right relationship with all beings. We base our values of good and bad on these ethics, which in turn help to determine good and ethical behavior in the world.

The role of catalytic change in the PDC

Part of the allure and impact of permaculture is it’s ability to be a source of meaning for people. The power of the permaculture design certification (PDC) course lies in it’s potential as a catalytic paradigm shift for the participants. In a PDC people often walk away with their worldview expanded, and they are given a solution set to help them adapt to a changing world. This is especially true of an in-person or “meatspace” course, as opposed to online. In the courses we teach with The Resilience Hub we often begin with the “Problem Game,” taught to us by our colleague Dave Jacke. It’s a cathartic exercise to let all the participants in the course talk about the problems of the world as they see them. Popcorn style, people talk in a sentence or two about the big problems in the world. They tend to fall into different categories of biodevastation, economic, political, technological, cultural and mythical problems. Then as a group we discuss how they are connected, and at some point we find that all these problems are connected at the cultural and mythical levels. As an exercise, it is a group catharsis to get all our anxieties off our chest and to look at the problems of the world full in the face and feel the gravity of the converging shitstorms of peak oil, climate change, economic contraction, resource wars, political/cultural upheaval, corporate greed & power, Big Brother, the Nanny State and so on.

If we do our jobs right as “facilitators of educational events” we change the course of people’s lives and give them a renewed sense of meaning and purpose in a chaotic world. If we do our jobs right, we leverage that catharsis to make it catalytic and initiate a permanent change in thought and behavior. More people are attracted to permaculture because of crisis at some scale whether that’s individual and personal or collective and societal. This makes sense given the decline and fall stage of empire we are seeing unfold now. While the physical “collapse” of empires takes an average of 200 years, collapse of meaning can happen much faster.

Meaning, purpose and religion as a category of human experience

It’s important not to understate the importance of meaning and purpose to a culture, and to consider the consequences when meaning and purpose collapse. In most individuals and societies, the wellspring of meaning and purpose comes not from rational or logical thought or understanding of the universe. Meaning and purpose come from narrative, metaphor and myth we generate as a result of inferring patterns out of the chaos of sensory stimuli from the universe. Pattern recognition is a deeply ingrained habit of the human mind. We then weave narratives about how these patterns relate to generate coherent stories as to WHY we are here and WHAT our purpose is in this absurd accident of existence.

I think of this deep source that generates meaning for our lives and sets of values regarding how we should act as “religious inspiration.” It is the ultimate source of human motivation and behavior. It is a significant force that shapes society and the material world. Try not to be too offended by my use of the word religion in this sense. I think that to be human is to be a religious animal, and even if the gods we worship are merely atoms, gravity, electrical forces and spirals of DNA; they still fill that devotional category of human experience. So I’m using religion broadly to refer to this deep wellspring of meaning, metaphysical narrative and purpose. For many people that involves one or many gods. For others, there are no gods but science, technology and a humanistic philosophy of progress to fill that same space. It is of critical importance to remember that many structures and normative behaviors of our society are inherited from a previous religious form. While the theistic aspects may have been stripped, the effect on meaning and purpose are the same. The myth/religion of progress is an example of such a non-theistic or civil religion.

Dimensions of religion as a category of human experience:

- Ethics and values like the “golden rule”

- Morals, concepts, behaviors like virtue, nobility, the good life

- Core beliefs that are seen as self-evidently good, true and sacred by which all standards of goodness and truth are measured.

- Sacred scriptures like the Bible or the Declaration of Independence

- Holy actors, saints and martyrs like Abraham Lincoln, John F Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr.

- Ceremony, formal rites and ritual drama like the pledge of allegiance and voting

- Binary opposition to it’s shadow form like Christianity/Satanism, Socialism/Capitalism, Progress/Apocalypse

Examples of civil religions:

- Marxism and socialism which are complete with a secular rapture they call “The Revolution,” as well as a strong evangelical component.

- Nationalism like Americanism with its historical exceptionalism and self-evidently positive notions of grandeur embodied in concepts like Manifest Destiny

- The myth of progress with its faith in Star Trek fantasies and a technology-based Rapture where we metamorphosize (or is it metastasize?) and expand across the solar system.

Assaulting the Myth of Progress

I’m focusing on a North American audience here based on my observations as a permaculture teacher and northeast regional network organizer. As a broad and general observation, Americans don’t like limits and have a deep faith-based commitment to the civil (non-theistic) religion of progress. I can even hear it in some permaculture discourse where people try to cast energy descent in progressive terms like, “A future of less energy could be better than the one we have now.” Again, I’m using religion here as a broad category of human experience from which we draw sources of deep meaning and values. Think of religion as an ultimate source of human motivation and behavior that explains our metaphysical position in the cosmos and gives us narrative meaning. It doesn’t have to be rational or conform to the real world. You can see religion as a force that shapes our thinking, behavior, society and the material world.

An explicit and central awareness of limits can be a helpful antidote to this religion of progress. As infrastructure, economy, democracy and basic respectful social relations break down, this causes a collapse of meaning in our lives. The world we’ve been conditioned to expect has not come to pass and a central organizing myth of our age is losing hold on our imagination and causing chaos. If anyone remembers the overly optimistic technological predictions from the 50’s and 60’s you might remember promises of nuclear power too cheap to be worth charging for, future generations earning more than their parents, weekend vacations to the moon and your own personal jetpack. It’s no wonder people are miffed—where are those jetpacks we were promised?!

If faith in progress is waning, if the ascendant god of the industrial age is dying, what then? Do we continue our collapse into nihilism or find a replacement? Both will likely occur in the short term (100 years or so). Whatever organizing principle of the imagination replaces faith in progress, it must be more adaptive to the existing conditions of decline and fall, brought to you by the twin shitstorms of climate chaos and energy peak.

As a central ethical feature of permaculture design, an awareness of and respect for limits acts as a helpful antidote to this blind faith in progress with greater explanatory power for the world we find ourselves in. After all:

- We are finite individuals with a finite life span

- We live on a finite planet with finite resources

- There are limits to how much I can know and understand

- There are limits to biodiversity imposed by climate and geography

- There are limits to the design process. At some point you must stop designing and begin implementing.

- There are limits to technique: you can’t put a swale and a hugel mound everywhere. Techniques are not universally applicable or appropriate.

- There are limits to industrial society, globalization, technology and democracy

Conclusion

There is a difference between growth, evolution and progress. Growth is a natural occurrence as any organism grows. Evolution can be beneficial when it is successful adaptation to ecological conditions. Progress in it’s highest narrative grandeur is seen as inevitable ascension toward higher forms of technological godliness where everyone gets to practice the “American Dream” of unlimited consumption. Discussion of limits is largely taboo here in industrialized North America, and so is a critique of progress. In economics there is only talk of growth and expansion (as if an ideology of cancer). In “progressive” politics social diversity, multiculturalism and openness are ends in and of themselves. In technology, it is a continuous rise of humanity from the caves to the stars. Mother Culture whispers in our ear that progress is inevitable and always good. It is taboo to disagree with the god-like thought form of progress. But that’s exactly why we should go where the taboo lies and interrogate. We should go where the shadow dwells (in the Jungian sense) to find that which is repressed or ignored. Evolution, power and wisdom could be a beneficial result. As children, limits are imposed from the outside, like from a parent or caregiver. As adults, limits and discipline are often self-imposed. As a society we need to develop sensible self-imposed limitations because if and when the Earth Mother imposes limitations on an industrial human culture grown too big for their britches, you can rest assured it will be a severe beat-down. Nature bats last, so the saying goes.

To revisit the image we started with of concentric rings with the ethics at the core, now we have the design principles, pattern literacy, strategies of implementation and techniques of management revolving around and bounded by these four ethics. Principles of good design and how to apply pattern literacy to design solutions closely follow the ethical core of permaculture. A strategic sequence of implementation is guided by clearly articulated goals and flows from principles and pattern fluency. Tools of installation and techniques of management form the final and most concrete aspects of this model. Note that tools and techniques find use once some amount of design thinking and strategic planning has occurred.

I submit to you that adding an awareness of limits as a discrete and explicit ethic of permaculture design provides a necessary antidote to the religion of progress found in many industrialized societies and will enhance our design practice and culture jamming work at this stage in our planetary history. This explicit ethic of bringing awareness to limits will help us re-member ecologically sensitive cultures rooted to living soil in the places we live. We stand for what we stand on.

I submit to you that adding an awareness of limits as a discrete and explicit ethic of permaculture design provides a necessary antidote to the religion of progress found in many industrialized societies and will enhance our design practice and culture jamming work at this stage in our planetary history. This explicit ethic of bringing awareness to limits will help us re-member ecologically sensitive cultures rooted to living soil in the places we live. We stand for what we stand on.

Jesse Watson is a permaculture designer, teacher and builder living and working in Rockland Maine, occupied Penobscot territory. He operates Midcoast Permaculture Design (midcoastpermaculture.com), serving residential, farm and institutional clients. He helps facilitate permaculture design certificate (PDC) courses with The Resilience Hub, based in Portland. He now serves on the board of directors of PAN, the Permaculture Association of the Northeast. He was instrumental in passing a locally binding food sovereignty ordinance in his town in May 2018 and likes to envision forest gardens in every backyard with reinvigorated and interdependent home economies.

Jason Daniels is a graphic designer living and working near the Salish Sea of Washington State. He created the illustrations in this article and you can follow him on Instagram.